- You are a Bishop, and a 17-year-old in your ward discloses to you that he has been smoking marijuana

- You are a ministering brother that has just been given a “special assignment” to help someone on welfare ween off welfare

- You are a Sunday School President that wants more members to attend Sunday School

- You are a Relief Society President that wants some women in the ward to take steps to improve their mental health

- You are an Elder’s Quorum President that wants some Perspective Elders to reengage with the gospel

- You are a High Priest Group Leader that needs more volunteers for a temple assignment

Our church, fueled by the gospel of Jesus Christ, puts us in positions to help others to change. We are literally change agents. The opportunities that we have to help others to learn, grow, contribute more, improve, develop, etc. are sacred. In many instances, we are God’s instruments. We are his eyes, hearts, and hands here to bless and help others.

But, here is a sticky question: Do you understand how to help others to change?

You see, we are change agents, but very few of us know and understand the principles of change, and in particular personal change.

But, do not get too discouraged because we are not alone. For a year, I worked with a management consulting company called Gallup, Inc. The primary job that Gallup consultants have is to help organizations and their leaders change. But, something I found interesting was that of all of the consultants that I worked with (roughly 50), there were only two that I had met that had actually read a book on change. What I realized is that Gallup had developed a process for initiating change that made it so that its consultants did not need to understand the science behind change in order for change to occur. But, what I also observed was that because its consultants did not understand the science behind change, they often presented information and recommendations that were suboptimal for organizational change, limiting the positive effect Gallup was having on its clients.

I think the same phenomenon happens within our church. The Church naturally creates a context that is conducive to change, but because most do not know and understand the principles of change, church leaders and change agents often make recommendations that are suboptimal for personal change.

Let me give you a personal example. Several years ago, I was given a special ministering assignment to assist a gentleman that had a variety of welfare issues. This gentleman was in a position where it was clear that he would be in need of welfare and church support indefinitely unless some rather large changes were made. I was excited about the opportunity to help this person, and I jumped right in with what I thought would be best. We initially did a financial assessment and put together a budget. We set some goals, and I continually followed up to see how he was doing on reaching his goals. To make a long story short, after over 18 months of working with this gentleman, he was not in any better of a place than when I had started working with him. Looking back on that experience, now that I have learned a thing or two about the science of change, it is clear to me that I was unable to help him make changes because I lacked basic understanding about how to facilitate change.

This experience has led me to study change so that I can be better able to help others when called upon. As I have studied change, I have learned two primary things:

- Change is a rich and deep topic, and

- There are some simple, yet core principles associated with change that can dramatically improve and shape how you help others to change.

Thus, the purpose of this article is not to give you a rich and deep understanding of change, but it is to deepen your understanding of change by conveying some core change principles, and thus empower you to become a more influential instrument in the hands of God. This will include discussing what our focus should be, a short discussion regarding methods that we should consider, and a summary of the Elephant-Rider-Path metaphor.

Focus

First, let us consider our focus. Obviously, our church has standards and norms for behavior, and if members’ behaviors fall below those standards or norms, we want to them to improve their behaviors up to an acceptable level. For example, if a youth is smoking marijuana, it is natural for us to focus on getting that youth to change his/her behaviors (i.e., get him/her to stop smoking).

Since behaviors are relatively easy to assess, measure, and/or evaluate, we are drawn naturally and powerfully into focusing solely on behaviors and on changing inappropriate behaviors. This draw is so powerful that it often overrides and overshadows the fact that repentance is not about behaviors. Repentance is about the things foundational to our behaviors: our minds and hearts (see Bible Dictionary definition of Repentance). Thus, if we are focusing on changing behaviors, we are operating and treating the issue at a surface level (queue band-aid analogy here).

Methods

Second, let us consider our methods. Ok, so you are wanting to change another’s mind and heart, and subsequent behaviors. What approach do you take? Research on influence tactics suggests that we are most likely to use rational arguments or pressure. For example, in the case of a youth smoking marijuana, we might use a rational argument by stating, “Smoking is really hazardous to your health, thus you should quit smoking;” or we might use pressure by stating, “If you don’t quit smoking, you are not going to be allowed to bless the sacrament.” Although these two influence tactics are the most commonly used, they have also been found to be the least helpful at initiating change. The reason why will become more apparent when we consider the three main factors involved in change. This leads us to the Elephant-Rider-Path metaphor.

Elephant-Rider-Path Metaphor

One the best and most digestible frameworks for understanding individual change is the Elephant-Rider-Path Metaphor. It was first discussed in The Happiness Hypothesis by Jonathan Haidt, and made more popular by Chip and Dan Heath, in their book on change: Switch.

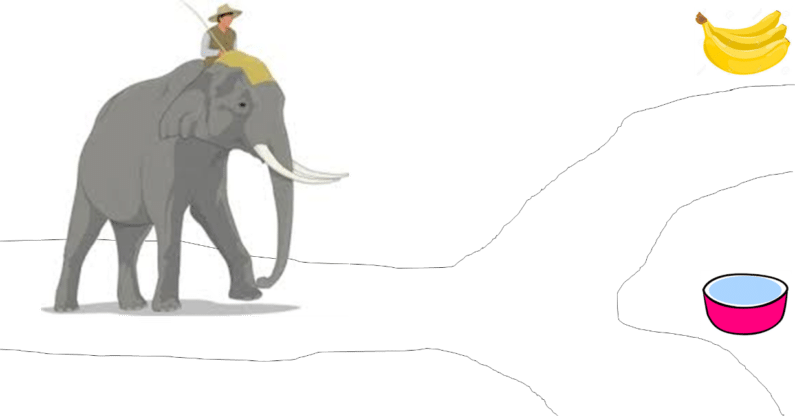

In the Elephant-Rider-Path Metaphor, there are three main elements: the elephant, the rider, and the path (see figure above). The elephant and rider combined represent us, with the elephant being our emotional side and the rider representing our rational side. The path represents the context or environment the elephant and rider find themselves in.

Before I dive into describing this metaphor, let me ask you a few questions:

- When you try to influence someone to change, do you try to appeal to the other person’s emotional side, the other person’s rational side, or do you try to change the other person’s environment?

- When a member of the Church is behaving in a way that falls below the standards of the Church, is that more likely because their emotional side is too strong, their rational side isn’t working properly, or because of the environment/context the person finds themselves in?

I think the answers to these questions will be enlightening.

Elephant & Rider. To more fully explain the metaphor, let me first introduce the elephant and the rider. As mentioned, these two combine to represent us, and each has its pros and cons in terms of the decisions we make and the behaviors we engage in. These are listed in the table below.

| Elephant – Emotional Side | Rider – Rational Side | |

| 1 | Large and strong | Small and weak |

| 2 | Eyes are focused on the ground | Eyes are elevated to see up ahead |

| 3 | Lazy and interested in short-term gains (instant gratification) |

Thoughtful and interested in long-term gains |

| 4 | Our home of love, compassion, sympathy, loyalty, etc. | Our home of logic |

| 5 | Brings power and energy to our actions | Tendency to overanalyze and overthink, slowing us down |

First, because of the size and strength difference between the elephant and the rider, the rider (our rational side, willpower) is limited in its abilities to control the elephant. Second & third, our elephant is the one that is taking steps and actually doing the walking. Thus, the elephant’s eyes are focused on what is immediately ahead, and is interested in saving/preserving its energy, making it lazy. Together, the elephant is a big proponent of instant gratification. Our rider, because of his position on top of the elephant, is able to take in a broader perspective and is able to devote energy to thinking rather than doing. As such, the rider is thoughtful, strategic, and interested in long-term gains and goals. Combining these facts suggest that when our elephant disagrees with our rider about what direction to go, the elephant generally wins out (think over-sleeping, overeating, procrastination, skipping the gym, etc.).

The details above may lead one to think that the elephant in us is “evil,” and that we need to suppress it. But, this should never be the case because our elephant is our home for love, compassion, sympathy, loyalty, etc. (along with a variety of negative feelings/emotions). In fact, our elephant is what brings power, energy, and passions to our actions. On the other hand, since our rider is our home for logic, it has a tendency to slow us down with the desire to overanalyze and overthink.

Path. But, that being said, I am going to argue that the Path is actually the most crucial element in the Elephant-Rider-Path metaphor. I say this for two reasons. First, by considering the path, we can more fully understand why individuals are thinking and behaving the way they are, improving our ability to be empathetic and treat the root of the behaviors (hearts and minds) rather than the behaviors themselves. Second, out of the three elements in the metaphor, changing and influencing the path is the element that is most likely to lead to actual change.

There are two primary aspects of the path that strongly influence the elephant and the rider (and most frequently, just the elephant): the ease of the path, and the reward associated with each path. Regarding the ease of the path, the elephant is lazy and seeks after instant gratification. Thus, if one path is obviously easier than another path (downhill versus uphill), the elephant is going to want to take the easiest route. Regarding the reward associated with each path, if the elephant has a certain need (e.g., thirsty), and the elephant has a choice between a path leading to water and a path leading to food, the elephant is going to want to take the path leading to water.

Thus, when an individual is engaging in a certain behavior that falls below the standards of the Church, it is usually because, to them, that path is easier than an alternative path and/or that path fulfills a need (be it emotional, spiritual, sexual, etc.).

Let me give you an example of this. I had an LDS friend in high school that came from a broken home, from which he carried some angst. Additionally, he had a difficult time finding a consistent group of friends, and he often felt left out and not accepted. Thus, when he happened to find himself being accepted with a group of kids who smoked marijuana, on one particular night when he was invited to smoke marijuana, he ultimately was faced with two paths: (1) a path that was easy (accepting the offer to smoke as opposed to denying the offer) and that fulfilled a need (having a group of friends that accepted him), and (2) a path that was difficult (denying the offer) and that did not fulfill a need (leaving/dropping his new group of friends). Naturally, he got into smoking marijuana.

I don’t know about you, but before I understood this metaphor, when someone was falling below the standards of the Church, I was inclined to think that it was because they weren’t strong enough. Or, more specifically, what I was really thinking was that their rider wasn’t strong enough. I failed to recognize the (1) power of the elephant, and (2) the crucial role the path plays in the person’s decision making and behaviors. For those familiar with psychology, this is called fundamental attribution error, which suggests that we have a tendency to explain others’ behaviors based upon internal factors (e.g., personality, disposition, laziness) as opposed to external factors (i.e., the path).

Now that I understand the power of the path, I now have greater understanding regarding why people act the way that they do, and I am much more empathetic toward them. I no longer rush to judgment when they fall short. Rather, I think, “what about their path or context led them to act the way they did.” Another way of saying this is that if we approach others believing that they are trying their very best, when someone does not live up to our approval, we will not look upon them with disdain, but with sympathy and empathy, thinking “what about your life led to you think or believe the way you do?” This allows us to love the person without necessarily condoning their behavior.

Even further, by understanding the power of the path, we are more prepared and equipped to help others to change. Take my marijuana-smoking friend for example. Naturally, if I wanted to help him stop smoking, I might take him to an addiction class (i.e., treating the behavior itself). But, if I recognize that the root of the problem is that he has an emotional need that is not being fulfilled, leading his elephant to go in a direction his rider may not approve of, then it becomes obvious that the best things I can do to help him change is to: (1) create a way to meet his emotional need, and (2) offer up easy alternative paths for meeting his emotional needs.

Finally, changing and influencing the path is the element that is most likely to lead to actual change. If we only focus on the rider or the elephant, but only the same paths present themselves, our influence on the rider or the elephant will still only result in the same outcomes. Thus, changing and influencing the path is the element that is most likely to lead to actual change.

Conclusion

So, when you are faced with helping:

- A 17-year-old to stop smoking marijuana…

- Someone on welfare ween off welfare…

- More members attend Sunday School…

- Members take steps to improve their mental health…

- Perspective Elders reengage with the gospel…

- Members engage more with the temple…

…what should be your focus and what should be your methods to positively influence those you are seeking to help change?

If you are like most people, we have a tendency of focusing on behaviors and engage in methods that appeal to the rider. Further, when we are diagnosing why people fall below the standards of the Church, we are more inclined to think that it is because of factors within them, and less inclined to consider the power and the pull associated with their environment (i.e., Path). If this is how we generally think when we are faced with an opportunity to help another change, it is not very likely that we are going to be able to effectively help them change and repent.

To be most effective in helping others to change, it is important that we focus, not on the behaviors, but on what is foundational to those behaviors. This includes:

- Directing the Rider (mind)

- Motivating the Elephant (heart)

- Understanding the needs of the Elephant in relation to alternative Paths

- Shaping the Path (environment)

While all of these four options play a role in the change process, out of the four options, we are going to be much more effective change agents if we seek to understand the environment the person is operating in, fulfill their needs, and make healthy and helpful paths more available and easier for them.

As I mentioned previously, I believe that we are God’s eyes, heart, and hands here to bless and help others. As such, we have the sacred opportunity to help others to change, to navigate life more successfully, and to live up to their divine potential. I hope that this article helps you to become a better change agent and instrument in God’s hands.

Ryan Gottfredson, Ph.D., is an assistant professor of Organizational Behavior and the Assistant Director of the Center for Leadership at the Mihaylo College of Business and Economics at California State University-Fullerton. His topical expertise is in leadership development, performance management, and organizational topics that include employee engagement, psychological safety, trust, and fairness. He holds a PhD in Organizational Behavior and Human Resources from Indiana University and a BA from Brigham Young University. Additionally, he is a former Gallup workplace analytics consultant, where he designed research efforts and engaged in data analytics to generate business solutions for dozens of organizations across various industries. He has published over 15 articles in various journals including Journal of Organizational Behavior, Journal of Management, Business Horizons, and Journal of Leadership and Organizational Studies.

This is very interesting and very helpful for leaders. Moreso because a lot of members are called but with not much leadership skills. It would be good if members could get this training

This is awesome Ryan!!

Hey! Thank you! Glad you liked it.

Afreakingmazing. Thank you so much for sharing your thoughts .